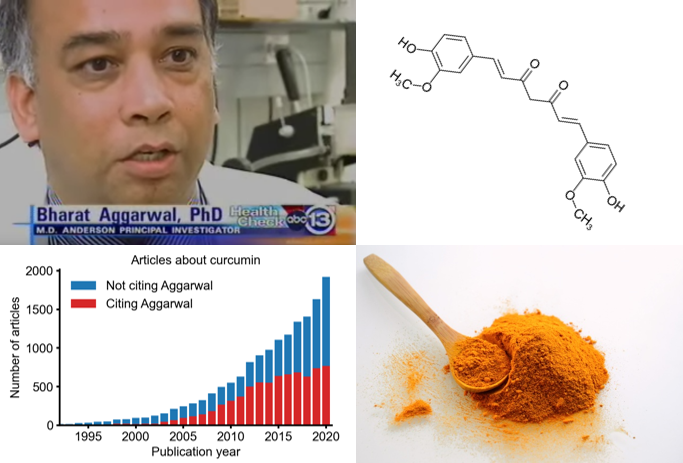

Bharat B. Aggarwal is an Indian-American biochemist who worked at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 1989 to 2015. His research focused on potential anti-cancer effects and therapeutic applications of herbs and spices. Aggarwal was particularly drawn to curcumin, a non-toxic compound found in turmeric that has long been staple in Ayurvedic systems of medicine. He authored more than 120 articles about the compound from 1994 to 2020. These articles reported that curcumin had therapeutic potential for a variety of diseases, including various cancers, Alzheimer’s disease and, more recently, COVID-19. In his 2011 book Healing Spices: How to Use 50 Everyday and Exotic Spices to Boost Health and Beat Disease, Aggarwal recommends “taking a daily 500 mg curcumin supplement for general health”.

Left: Chemical structure of curcumin in its keto form. Right: turmeric powder.

MD Anderson Cancer Center initially appeared to be fully on board with Aggarwal’s work. At one point, their website’s FAQ page recommended visitors buy curcumin wholesale from a company for which Aggarwal was a paid speaker (see “Spice Healer”, Scientific American). However, in 2012 (following observations of image manipulation raised by pseudonymous sleuth Juuichi Jigen), MD Anderson Cancer Center launched a research fraud probe against Aggarwal which eventually led to 30 of Aggarwal’s articles being retracted. Only some of these studies were about curcumin specifically, but most concerned similar natural products.

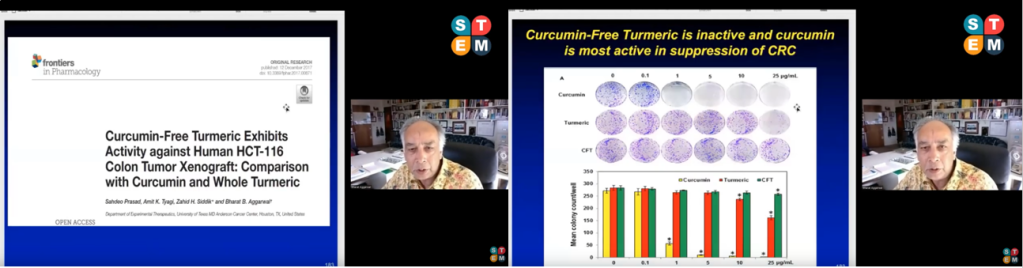

Retractions rarely number this high for a single author; according to the Retraction Watch leaderboard, only 26 other people have authored this many retracted studies. Aggarwal’s retracted articles feature dozens of instances of spliced Western blots and duplicated images, as well as several instances where mice were implanted with tumors exceeding volumes considered ethical. PubPeer commenters have noted irregularities in many publications beyond the 30 that have already been retracted. Aggarwal retired from M.D. Anderson in 2015, but has continued to author articles and appear at conferences.

Aggarwal citing a 2017 paper he wrote, retracted in 2018, in a 2022 conference presentation.

Curcumin doesn’t work well as a therapeutic agent for any disease. Though it is safe for human consumption in most forms and will show activity in essentially any in vitro assay you throw at it (via a process known as assay interference), no well-powered clinical trials have ever found it to be an effective medicine. Consider the following summary from Nelson et al. 2017:

“[No] form of curcumin, or its closely related analogues, appears to possess the properties required for a good drug candidate (chemical stability, high water solubility, potent and selective target activity, high bioavailability, broad tissue distribution, stable metabolism, and low toxicity). The in vitro interference properties of curcumin do, however, offer many traps that can trick unprepared researchers into misinterpreting the results of their investigations.”

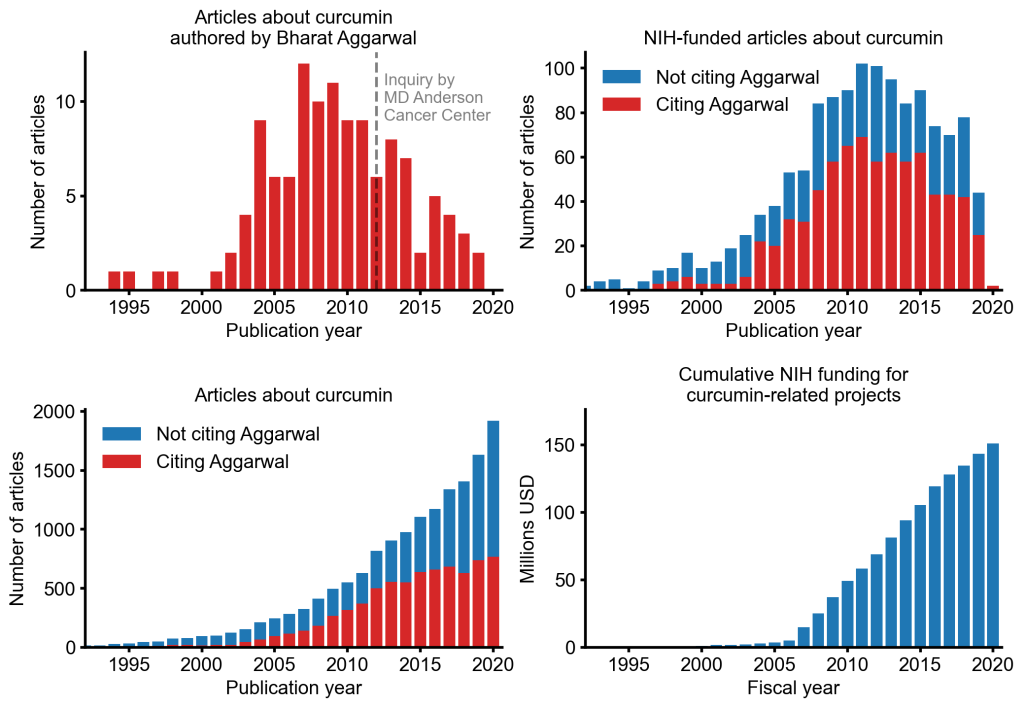

Despite curcumin’s apparent lack of therapeutic promise, the volume of research produced on curcumin grows each year. More than 2,000 studies involving the compound are published annually. Many of these studies bear signs of fraud and involvement of paper mills. As of 2020, the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) has spent more than 150 million USD funding projects related to curcumin. Funding increased drastically in the 2007 fiscal year, shortly after Aggarwal began to publish in earnest about the compound and the same year he declared curcumin “the Indian solid gold”.

Graphs describing the volume of curcumin research from various sources. Data collected from PubMed and NIH RePORTER. Data may be incomplete in recent years.

This proliferation of research on curcumin has fueled its popularity as a dietary supplement. Grand View Research estimated the global market for curcumin as a pharmaceutical to be around 30 million USD in 2020. Manufacturers are routinely scolded by the United States Food and Drug Administration for making false claims about the health effects of these supplements.

Curcumin is a valuable case study in how unimpeded fraud can distort an entire research field to the detriment of genuine research. Despite indications that Aggarwal’s research on curcumin ought not to be considered reliable, a majority of articles and an even greater majority of NIH-funded studies about curcumin still cite Aggarwal’s work. It seems unlikely that this explosion in funding and research would have materialized if Aggarwal had not engaged in large-scale research fraud.

Scientific fraud, especially at this scale, is alarming. However, there is a common refrain that instances like this are an exceedingly rare, insular threat and that any harm done to human knowledge by them will inevitably be neutralized by science’s remarkable tendency for self-correction. Once the history books are written, these instances will be little more than footnotes, parked between the Bates method and orgone.

However, self-correction has a high cost in the present: hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars, countless hours spent toiling by junior scientists, thousands of laboratory animals sacrificed, thousands of cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials for ineffective treatments, and countless people who have eschewed expensive and invasive but effective cancer treatment in favor of a store-bought spice, encouraged by research steeped in lies.

https://bxt.org/5siqn